1 TL;DR

Dates/times are the last type of data you’ll probably work with on a fairly regular basis. This post will show you how to use the lubridate tidyverse package in R so you’ll know how to handle dates & times when you encounter them.

image source: https://www.pxfuel.com/

2 Introduction

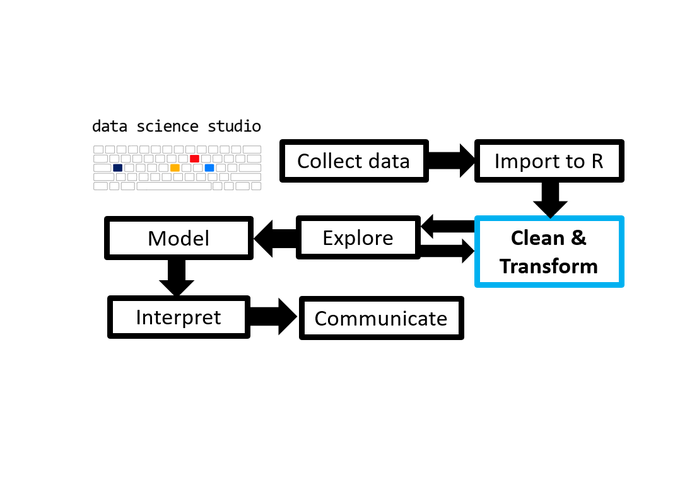

The 9th post of the Scientist’s Guide to R series covers how to work with dates and times in R. This will be the last post on data structures in R that we need to cover before we can confidently move on to more exciting things.

Until I learned about the lubridate package, dates were one of the most frustrating data structures to work. This is partly because there are many different formats that can be used to specify them and it’s not uncommon for multiple formats to be used within the same dataset if more than one person entered the data. To make things worse, when you import data from Excel dates will often be read as 5-digit numbers that can leave you wondering if the data somehow became corrupted. Part of the reason for this strangeness is that different programs use different date origins (thanks to my fellow DSS blogger Andriy Koval for pointing that out). For example, as you’ll see below, R uses January 1st of 1970 as an origin whereas Excel uses January 1st of 1900.

This post will show you how lubridate can help you overcome these sorts of problems. I’ll also demonstrate how lubridate can help you plan experiments.

2.1 load packages

As usual, we’ll start by loading the packages we’ll need.

library(tidyverse) #as usual, we'll need to use some tidyverse packages

#while it is part of the "tidyverse", `lubridate`is installed and loaded

#separately from the tidyverse meta-package

#install.packages("lubridate") #uncomment and run if you haven't installed it before

library(lubridate) 3 date/time basics

In R, temporal data can be represented as dates, times (within a day), or a combination of a date and a time (date-time)1. If your data are stored as a tibble, these types will have different class labels: “date”, “time” and “dttm” respectively. Otherwise, they’ll be classified using a date/time format called “POSIXct” (stands for portable operating system interface [originally designed for UNIX], chronological time). There is also a “local time” version which has to do with time zones, but we won’t worry about it for now. Each of these date/time object types has a slightly different default display format (“default” because lubridate allows you to modify it) that determines how the values are displayed:

dates: yyyy-mm-dd (year-month-day)

times: hh:mm:ss (hours:minutes:seconds)

datetimes: yyyy-mm-dd hh:mm:ss

at the right end of times/datetimes you’ll also see an abbreviation for the time zone, which will be “UTC” by default. I’ll cover time zone details later in this post.

Under the hood, a date object in R is stored as the number of days from January 1st of 1970, which is revealed if you convert a date to a numeric vector.

as.Date("1970-01-01") %>%

as.numeric()## [1] 0as.Date("1970-01-02") %>%

as.numeric()## [1] 1as.Date("2020-08-29") %>%

as.numeric()## [1] 18503Wow, it’s been a lot of days since January 1st of 1970.

Why does R represent dates internally as integers? So you can do quick calculations with them, e.g. to get the date 100 days from August 29th, 2020:

as.Date("2020-08-29") + 100## [1] "2020-12-07"Calculating the number of days between 2 dates is also pretty straightforward, just subtract the earlier one from the later one:

as.Date("2020-08-29") - as.Date("2020-01-01")## Time difference of 241 days4 which day is it?

In base R, you can also get today’s date using Sys.Date()

Sys.Date()## [1] "2020-10-10"Or using the easier-to-remember lubridate function today()

today()## [1] "2020-10-10"You can also get the current system date & time using base::Sys.time() or lubridate::now()

Sys.time()## [1] "2020-10-10 00:20:37 EDT"now()## [1] "2020-10-10 00:20:37 EDT"5 reading dates

While we didn’t have any trouble turning a string into a date when it was presented in the standard format “yyyy-mm-dd”, things go awry if we try the same thing with a non-standard format like “dd-mm-yyyy”:

as.Date("29-08-2020") %>% as.numeric()## [1] -708704Well that doesn’t look right!

To use a non-standard format with as.Date() we’ll need to specify it with the format argument via a combination of case-sensitive %* (replace * with the appropriate letter) codes of the form "%Y-%m-%d", where the most common ones you may need are:

%a= abbreviated weekday name%A= full weekday name%b= abbreviated month name%B= full month name%d= day of the month as a 2-digit number%D= shortcut for%Y/%m/%d%e= day of the month as a single digit number with a leading space%Hor%I= hours as a 2-digit number%j= day of the year as a 3-digit number%m= month as a 2-digit number%M= Minute as a 2-digit number%p= AM/PM indicator to use in conjuction with hours specified via%Ibut not%H%S= seconds as a 2-digit number%U= week of the year as a 2-digit number (using Sunday as day 1 of the week)%T= shortcut for%H:%M:%S%y= year without the century (2-digits)%Y= year with the century%Z= time zone abbreviation as a character string

See the strptime help documentation for more information on these codes and a complete list using ?strptime

To correctly parse “29-08-2020” as day-month-year using as.Date() we would therefore need to specify the format as follows:

dt <- as.Date("29-08-2020", format = "%d-%m-%Y")

dt ## [1] "2020-08-29"dt %>% as.numeric()## [1] 18503Now it shows up the way we expected, and is correctly represented internally as 18,503 days since January 1st of 1970 (as before) rather than -708,704.

As you can see, this could make date processing quite tedious, especially if you don’t work with dates or times very often or if your data use multiple formats! This is an example of the kinds of hassle that lubridate was created to help us overcome. Instead of having to specify the format using %*-codes, lubridate has a set of functions that make it easy to read dates in various string formats that you may encounter in raw data and convert them to the standard format

ymd()year, month, daydmy()day, month, yearmdy()month, day, year

These parsing functions make it quite easy to read dates, e.g.

identical(

ymd("2020-08-29"),

dmy("29-08-2020")

)## [1] TRUEidentical(

ymd("2020-08-29"),

mdy("08-29-2020")

)## [1] TRUEIf you also need to specify the time, there are extensions for the above convenience functions to make that easy too. Add _h for hours, _hm for hours & minutes, and _hms for hours, minutes, and seconds, e.g.:

ymd_h("2020-08-29 22")## [1] "2020-08-29 22:00:00 UTC"dmy_hm("29-08-2020 22:09")## [1] "2020-08-29 22:09:00 UTC"mdy_hms("08-29-2020 22:09:19")## [1] "2020-08-29 22:09:19 UTC"Since working with datetimes is considerably easier in lubridate than base R, for the sake of brevity I’ll focus on the lubridate approach for most of the remainder of this post. If you would like to learn more about working with datetimes in base R, see this link.

Fortunately, these lubridate functions can also handle a variety of non-numeric characters between the datetime values and still parse them correctly.

ymd("2020-08-29") == ymd("2020/08/29") ## [1] TRUEymd("2020-08-29") == ymd("2020 08 29")## [1] TRUEymd("2020-08-29") == ymd("2020:08:29")## [1] TRUEymd("2020-08-29") == ymd("2020$08$29")## [1] TRUE6 time zones

To specify the time zone we can use the tz argument:

ymd_h("2020-08-29 9",

tz = "America/Vancouver") # tz = Continent/City## [1] "2020-08-29 09:00:00 PDT"For example, you could use this to figure out what the time difference is between New York and London or Vancouver and Cairo

ymd_h("2020-08-29 9", tz = "America/New_York") - ymd_h("2020-08-29 9", tz = "Europe/London") ## Time difference of 5 hoursymd_h("2020-08-29 9", tz = "America/Vancouver") - ymd_h("2020-08-29 9", tz = "Africa/Cairo") ## Time difference of 9 hoursA list of time zone names can be found on this wikipedia page.

7 month names

lubridate functions can even parse the month names if they’re provided instead of a fully numeric date string.

mdy("October 31st, 2020")## [1] "2020-10-31"dmy("the 1st of December 2011")## [1] "2011-12-01"8 extracting datetime components

lubridate also provides a number of self-explanatory functions for extracting some of the information from a date or datetime:

dt <- ymd_hms("2020-08-29 22:09:19")

year(dt)## [1] 2020month(dt)## [1] 8day(dt)## [1] 29hour(dt)## [1] 22minute(dt)## [1] 9second(dt)## [1] 19week(dt) #week of the year## [1] 35wday(dt) #day of the week, numeric## [1] 7wday(dt,#day of the week

label = TRUE, #as a factor level

abbr = FALSE) #not abbreviated## [1] Saturday

## 7 Levels: Sunday < Monday < Tuesday < Wednesday < Thursday < ... < Saturday#day of the month, this one isn't really useful since it gives you the same

#thing as day()

mday(dt) ## [1] 29yday(dt) #day of the year## [1] 2429 days in a month

There is also a lubridate function which tells you how many days there are in a specified month if you haven’t yet memorized them all.

days_in_month(dt) #the month specified in a datetime object## Aug

## 31days_in_month(3) #or whichever month you want to specify## Mar

## 31days_in_month(1:12) #or all months at once## Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec

## 31 28 31 30 31 30 31 31 30 31 30 3110 custom date formats

If you’d prefer to have dates displayed differently from the standard/default yyyy-mm-dd format, you can specify an alternative format to use with the lubridate::stamp_date() function. This could be useful if you want the dates to follow a specific format that is used in your lab or workplace.

#step 1: specify the format using an arbitrary date with stamp_date()

my_stamp <- stamp_date("January 7th, 2019")

#step 2: apply the format to a date object

my_stamp(dt)## [1] "August 29th, 2020"#if there are multiple possibilities lubridate will use the most probable/common oneThe alternative way of changing the display format is to apply the base R format() function to a datetime object and specify the format using the %-codes, e.g.

format(dt, "%B %dth, %Y")## [1] "August 29th, 2020"Again, the lubridate version is a bit easier.

11 date calculations

You can add days to a date that’s been processed using lubridate just as easily as we did using the base R as.Date() function

dt <- ymd("2020/08/30")

dt + 10## [1] "2020-09-09"A raw number added to a date is interpreted as a request to add the smallest unit of time to the object that is already represented in it. You could instead specify the unit to add (weeks, month, years, etc) to a date with some intuitively-named lubridate helper functions:

ymd("2020/08/30") + 10 #adds 10 days## [1] "2020-09-09"ymd_hms("2020/08/30 10:12:58") + 10 #adds 10 seconds## [1] "2020-08-30 10:13:08 UTC"ymd_hms("2020/08/30 10:12:58") + days(10) #adds 10 days instead of seconds## [1] "2020-09-09 10:12:58 UTC"ymd("2020/08/30") + weeks(1) #adds 1 week## [1] "2020-09-06"ymd("2020/08/30") - months(100) #subtracts 100 months## [1] "2012-04-30"ymd("2020/08/30") + years(80) #adds 80 years## [1] "2100-08-30"N.B. As was recently pointed out by one of my talented colleagues, Sam Albers, if you’re adding months() to 29th or later day of the month and the new date doesn’t exist you’ll get an NA value, e.g.

ymd("2020-10-31") + months(1)## [1] NAThere is no November 31st, so an NA is returned. If we were hoping to get a sensible result like the 30th of November or 1st day of December we’d be disappointed. To fix this and get the nearest day (rounded down), you should instead use the lubridate %m+% operator, or the add_with_rollback() function.

ymd("2020-10-31") %m+% months(1)## [1] "2020-11-30"add_with_rollback(ymd("2020-10-31"), months(1))## [1] "2020-11-30"To roll forward instead of backwards, we can also use add_with_rollback() but this time we set the roll_to_first argument to TRUE

add_with_rollback(ymd("2020-10-31"), months(1), roll_to_first = TRUE)## [1] "2020-12-01"Alongside %m+% is a %m-% operator that subtracts months without rolling over to another month.

You can even add vectors of set intervals. For example, if you had a weekly meeting for the next 10 weeks and wanted to know the dates of each of them, you could use:

ymd("2020/08/30") +

weeks(1)*c(1:10) #1 week unit for the interval * vector of meeting indices/values## [1] "2020-09-06" "2020-09-13" "2020-09-20" "2020-09-27" "2020-10-04"

## [6] "2020-10-11" "2020-10-18" "2020-10-25" "2020-11-01" "2020-11-08"#if you were given a vector of dates and wanted to know which days of the week

#they fell on you can easily get that too. e.g. if you had a meeting on the 15th

#of every month...

meeting_dates <- ydm(

stringr::str_c("2020-15-", 1:12)

)

meeting_dates## [1] "2020-01-15" "2020-02-15" "2020-03-15" "2020-04-15" "2020-05-15"

## [6] "2020-06-15" "2020-07-15" "2020-08-15" "2020-09-15" "2020-10-15"

## [11] "2020-11-15" "2020-12-15"meeting_dates %>% wday(label = TRUE)## [1] Wed Sat Sun Wed Fri Mon Wed Sat Tue Thu Sun Tue

## Levels: Sun < Mon < Tue < Wed < Thu < Fri < Sat#or you could apply a date_stamp to them, which could be useful for populating

#an excel report or data collection sheet.

my_stamp <- stamp_date("Monday, January 7th, 2019")

meeting_dates %>% my_stamp()## [1] "Wednesday, January 15th, 2020" "Saturday, February 15th, 2020"

## [3] "Sunday, March 15th, 2020" "Wednesday, April 15th, 2020"

## [5] "Friday, May 15th, 2020" "Monday, June 15th, 2020"

## [7] "Wednesday, July 15th, 2020" "Saturday, August 15th, 2020"

## [9] "Tuesday, September 15th, 2020" "Thursday, October 15th, 2020"

## [11] "Sunday, November 15th, 2020" "Tuesday, December 15th, 2020"You can also get the interval between two dates in the unit(s) of your choice using the lubridate::interval() & lubridate::time_length() functions together.

#step 1: define an interval using lubridate::interval()

int <- interval(mdy("12-01-2005"), today())

#step 2: use time_length(interval) and the "unit" argument

time_length(int, unit = "day") #interval length in days## [1] 5427time_length(int, unit = "month") #interval length in months## [1] 178.2903time_length(int, unit = "year") #interval length in years## [1] 14.85792time_length(int, unit = c("day", "week", "month", "year")) #you can also ask for multiple formats at once## Warning in if (unit %in% c("year", "month")) {: the condition has length > 1 and

## only the first element will be used## [1] 5427.00000 775.28571 178.29979 14.85832interval(ymd_h("2020-08-27 10"), now()) %>%

time_length(unit = "hour") #interval length in hours## [1] 1050.344#of course you can also get the difference in days by just subtracting one date

#from the other as we did earlier using base R functions

mdy("12-10-2005") - mdy("12-01-2005")## Time difference of 9 days11.1 correcting excel date-to-numeric conversions

Although it isn’t part of lubridate, there is a function from the janitor package called excel_numeric_to_date() that can help. For example, May 20th of 2016 may have looked like “2016-05-20” in the .xlsx file when you looked at it, but then when it gets imported into R, it appears as the mysterious number 42510 instead. This is an unfortunate issue that sometimes occurs when trying to read data from excel files specifically. The excel_numeric_to_date() simply converts these 5-digit date codes back to the string date format you were expecting.

janitor::excel_numeric_to_date(42510)## [1] "2016-05-20"#also works with vectors

janitor::excel_numeric_to_date(

c(42510:42520)

)## [1] "2016-05-20" "2016-05-21" "2016-05-22" "2016-05-23" "2016-05-24"

## [6] "2016-05-25" "2016-05-26" "2016-05-27" "2016-05-28" "2016-05-29"

## [11] "2016-05-30"12 planning a behavioural neuroscience experiment

Before I transitioned to working as a data scientist for the BC Government I spent some time doing behavioural neuroscience research. One of the first things I needed to do to conduct an experiment was figure out when I needed to do different things in the lab. I used R to make this process easier and help sort out which days I would need to reserve lab equipment and other resources.

I started by defining some key parameters such as the sample size per group and the number of treatment conditions I planned to use in my design. These parameters mattered because they would determine how many days some aspects of the experiment would take.

For this demo, we’ll plan an experiment with rats that uses an aerobic exercise intervention (for half of the animals, selected at random) that lasts 4 weeks, followed by 7 days of behavioural testing in the Barnes Maze (a test of spatial learning and memory for rodents), and then electrophysiological slice recordings to see if we can pickup any changes in neural signalling that might be related to the behavioural effects of the exercise intervention. Feel free to copy this script and adapt it for your own purposes.

To plan out this hypothetical experiment, we’ll need to define some parameters of the study design that affect scheduling, summarized as follows:

most obviously, which day we plan to start the experiment

the desired sample size and number of experimental groups, which may affect how long some parts of the experiment take based on the available lab equipment (e.g. the number of electrophysiology rigs in the lab)

whether or not we’ll be breeding the model species we need (rats in this case) or ordering it

how many days our experimental intervention or treatment will take to administer

how many days our Barnes maze protocol is

if we’re measuring neural activity in this experiment using electrophysiology, and how many rigs we plan to use at once

Then we’ll need to perform the necessary operations on those parameters using a combination of functions from lubridate, functions from tidyverse packages we’ve seen in previous posts, and a bit of base R code.

To semi-automate this process, a first code block can be used to define parameters and a second one can describe the operations we need to perform on them.

#sample parameters####

#how many total experimental groups will be included; if you're planning to use

#both sexes and consider biological sex as a factor in your analyses double it.

n.groups <- 4

#desired sample size. This is something to discuss with your PI, but I usually

#tried to aim for at least 12 when examining behaviour

group.n <- 12

#timing parameters####

#to generate animals, start breeding 1 month before experiment begins. replace

#with desired start day, month, and year

start.date <- dmy("07-09-2020")

breeding <- TRUE #will you be breeding the animals needed for this experiment?

#if you aren't breeding animals, I'll assume they are being ordered from a

#commercial breeder, in which case we'll use the estimated delivery date as the

#start date

intervention_days <- 28 #how many days will the experimental intervention take?

b.testing_days <- 7 #how many days will the behavioural testing take?

#Are you doing electophysiology? Estimate about 2 days per animal per

#available e-phys rig

ephys <- TRUE

ephys.rigs <- 4

#display parameter####

#provide an example of how you would like the dates displayed

my_stamp <- stamp_date("Saturday, August 29th, 2020") From this point we can just run the script below and we’ll end up with an approximate schedule for our hypothetical behavioural neuroscience experiment. Don’t worry too much about the details of the conditional (if, else if, else) statements, we’ll cover that in a later post on R programming, although below we’ll take a first look at how to define a function.

exp_timeline <- list() #define a list to hold experimental protocol components

#animal breeding####

#we'll store a version with modified display formatting separately so we can

#still perform calculations on d0

exp_timeline[["start_date"]] <- my_stamp(start.date)

if(breeding == TRUE) {

dob <- start.date+28 #pups born

exp_timeline[["pups_born"]] <- my_stamp(dob)

#approximate weaning date####

wd <- dob + 21

exp_timeline[["pups_weaned"]] <- my_stamp(wd)

}

#acclimatization period####

#acclimatization to maternal separation (if bred in house) or arrival at the

#animal facility (if ordered) (usually 1 week). After this point your animals

#are ready to participate in a behavioural experiment

if(breeding == TRUE) {

ready.date <- wd + 7

exp_timeline[["ready_date"]] <- my_stamp(ready.date)

} else {

ready.date <- start.date + 7

exp_timeline[["ready_date"]] <- my_stamp(ready.date)

}

#intervention protocol####

if (intervention_days > 0) {

i.ds <- ready.date + c(1:intervention_days)

exp_timeline[["intervention"]] <- data.frame("protocol_day" = str_c("day #",

c(1:intervention_days)),

"date" = my_stamp(i.ds))

}

#behavioural testing days####

#starting the day after the intervention is complete. if you haven't been

#handling the animals throughout the intervention period for at least 1 week

#then add as many days as needed to ensure the animals have been handled for at

#least 1 week

if (b.testing_days > 0) {

if (intervention_days > 0) {

if (intervention_days < 7) {

handling_days <- 7 - intervention_days

h.ds <- i.ds[intervention_days] + c(1:handling_days)

b.ds <- h.ds[handling_days] + c(1:b.testing_days)

} else {

b.ds <- i.ds[intervention_days] + c(1:b.testing_days)

}

} else if (intervention_days == 0) {

#if you were just doing behavioural testing an no postnatal intervention

#e.g. for a transgenic to wild-type model comparison

#add a week for handling where they should be handled for at least 1 minute

#each per day for at least 5 of the days in the "handling" week

handling_days <- 7

h.ds <- ready.date + c(1:handling_days)

b.ds <- h.ds[7] + c(1:b.testing_days)

}

if (exists("h.ds")) {

exp_timeline[["animal_handling"]] <- data.frame("protocol_day" = str_c("day #",

c(1:handling_days)),

"date" = my_stamp(h.ds))

}

exp_timeline[["behavioural_testing"]] <- data.frame("protocol_day" = str_c("day #",

c(1:b.testing_days)),

"date" = my_stamp(b.ds))

}

#electrophysiology days###

#for an exercise intervention study we could start doing e-phys the day after behavioural testing is complete

totaln <- n.groups*group.n #need to know how many total animals there are

if (ephys == T) {

ephys.days <- (totaln/2)/ephys.rigs

if (b.testing_days > 0) {

e.ds <- b.ds[b.testing_days] + c(1:ephys.days)

} else if (b.testing_days == 0 & intervention_days > 0) { #if you only did an intervention

e.ds <- i.ds[intervention_days] + c(1:ephys.days)

} else if (b.testing_days == 0 & intervention_days == 0) { #if you're only doing e-phys

e.ds <- ready.date + c(1:ephys.days)

}

exp_timeline[["electrophysiology"]] <- data.frame("protocol_day" = str_c("day #",

c(1:ephys.days)),

"date" = my_stamp(e.ds))

}

#determine how many days the experiment will take to complete up to the end of data collection####

if (exists("e.ds")) {

exp_timeline[["total_days"]] <- e.ds[ephys.days] - start.date

} else if (exists("b.ds")) {

exp_timeline[["total_days"]] <- b.ds[b.testing_days] - start.date

} else if ("i.ds") { #if you only used an intervention and finished collecting data when it was over

exp_timeline[["total_days"]] <- i.ds[intervention_days] - start.date

} After defining the parameters to use in constructing our experimental timeline and running the script, all we have to do to see it is print it to the console:

exp_timeline## $start_date

## [1] "Monday, September 07th, 2020"

##

## $pups_born

## [1] "Monday, October 05th, 2020"

##

## $pups_weaned

## [1] "Monday, October 26th, 2020"

##

## $ready_date

## [1] "Monday, November 02th, 2020"

##

## $intervention

## protocol_day date

## 1 day #1 Tuesday, November 03th, 2020

## 2 day #2 Wednesday, November 04th, 2020

## 3 day #3 Thursday, November 05th, 2020

## 4 day #4 Friday, November 06th, 2020

## 5 day #5 Saturday, November 07th, 2020

## 6 day #6 Sunday, November 08th, 2020

## 7 day #7 Monday, November 09th, 2020

## 8 day #8 Tuesday, November 10th, 2020

## 9 day #9 Wednesday, November 11th, 2020

## 10 day #10 Thursday, November 12th, 2020

## 11 day #11 Friday, November 13th, 2020

## 12 day #12 Saturday, November 14th, 2020

## 13 day #13 Sunday, November 15th, 2020

## 14 day #14 Monday, November 16th, 2020

## 15 day #15 Tuesday, November 17th, 2020

## 16 day #16 Wednesday, November 18th, 2020

## 17 day #17 Thursday, November 19th, 2020

## 18 day #18 Friday, November 20th, 2020

## 19 day #19 Saturday, November 21th, 2020

## 20 day #20 Sunday, November 22th, 2020

## 21 day #21 Monday, November 23th, 2020

## 22 day #22 Tuesday, November 24th, 2020

## 23 day #23 Wednesday, November 25th, 2020

## 24 day #24 Thursday, November 26th, 2020

## 25 day #25 Friday, November 27th, 2020

## 26 day #26 Saturday, November 28th, 2020

## 27 day #27 Sunday, November 29th, 2020

## 28 day #28 Monday, November 30th, 2020

##

## $behavioural_testing

## protocol_day date

## 1 day #1 Tuesday, December 01th, 2020

## 2 day #2 Wednesday, December 02th, 2020

## 3 day #3 Thursday, December 03th, 2020

## 4 day #4 Friday, December 04th, 2020

## 5 day #5 Saturday, December 05th, 2020

## 6 day #6 Sunday, December 06th, 2020

## 7 day #7 Monday, December 07th, 2020

##

## $electrophysiology

## protocol_day date

## 1 day #1 Tuesday, December 08th, 2020

## 2 day #2 Wednesday, December 09th, 2020

## 3 day #3 Thursday, December 10th, 2020

## 4 day #4 Friday, December 11th, 2020

## 5 day #5 Saturday, December 12th, 2020

## 6 day #6 Sunday, December 13th, 2020

##

## $total_days

## Time difference of 97 daysVoila! There you have it. If you were doing this experiment, you’d know approximately which days each step of the protocol would fall on and how long it would take to get your data!

12.1 turning the planning script into a function

If we ran these sorts of experiments frequently, eventually we would probably want to combine these pieces into a custom scheduling function. While having all of the code in the script provides full transparency, it also makes the method a bit fragile (especially if you’re not using version control [you should always use some form of version control to save your work!]). Writing a function, documenting it, and putting it into a package is a much better (and more easily shared) long term option. The source code of an R function can of course still be inspected after all.

Functionalizing our experiment planning script actually isn’t too much extra work once we’ve gotten this far. We basically just need to convert the “parameter definitions” code block into a set of arguments to the special base R function, "function()", copy and paste the “operations” code block into the function body, and assign a name to the result. For this example, I’ll use the name “plan_bn_exp” (for “plan a behavioural neuroscience experiment”).

plan_bn_exp <- function(#call function() & assign to desired name

#then specify arguments the user can modify between the parentheses

#note: the ones without a default value, set using`=` (as below), require the user

#to specify a value

start_dmy, #this name makes it clear which format to use

intervention_days,

behav_days,

n_groups,

group_n,

#if some of these don't change very often between

#experiments, you might want to set default values for

#them

date_stamp = "Saturday, August 29th, 2020",

breeding = TRUE,

ephys = TRUE,

ephys_rigs = 4

) {

#then in the section between the curly braces {}, called the "body" of the

#function, you define what happens to the argument inputs, which in this case

#just means copying/pasting the relevant code block from above

start.date <- dmy(start_dmy)

exp_timeline <- list()

exp_timeline[["start_date"]] <- my_stamp(start.date)

if(breeding == TRUE) {

dob <- start.date+28

exp_timeline[["pups_born"]] <- my_stamp(dob)

wd <- dob + 21

exp_timeline[["pups_weaned"]] <- my_stamp(wd)

}

if(breeding == TRUE) {

ready.date <- wd + 7

exp_timeline[["ready_date"]] <- my_stamp(ready.date)

} else {

ready.date <- start.date + 7

exp_timeline[["ready_date"]] <- my_stamp(ready.date)

}

if (intervention_days > 0) {

i.ds <- ready.date + c(1:intervention_days)

exp_timeline[["intervention"]] <- data.frame("protocol_day" = str_c("day #",

c(1:intervention_days)),

"date" = my_stamp(i.ds))

}

if (b.testing_days > 0) {

if (intervention_days > 0) {

if (intervention_days < 7) {

handling_days <- 7 - intervention_days

h.ds <- i.ds[intervention_days] + c(1:handling_days)

b.ds <- h.ds[handling_days] + c(1:b.testing_days)

} else {

b.ds <- i.ds[intervention_days] + c(1:b.testing_days)

}

} else if (intervention_days == 0) {

handling_days <- 7

h.ds <- ready.date + c(1:handling_days)

b.ds <- h.ds[7] + c(1:b.testing_days)

}

if (exists("h.ds")) {

exp_timeline[["animal_handling"]] <- data.frame("protocol_day" = str_c("day #",

c(1:handling_days)),

"date" = my_stamp(h.ds))

}

exp_timeline[["behavioural_testing"]] <- data.frame("protocol_day" = str_c("day #",

c(1:b.testing_days)),

"date" = my_stamp(b.ds))

}

totaln <- n.groups*group.n

if (ephys == T) {

ephys.days <- (totaln/2)/ephys.rigs

if (b.testing_days > 0) {

e.ds <- b.ds[b.testing_days] + c(1:ephys.days)

} else if (b.testing_days == 0 & intervention_days > 0) {

e.ds <- i.ds[intervention_days] + c(1:ephys.days)

} else if (b.testing_days == 0 & intervention_days == 0) {

e.ds <- ready.date + c(1:ephys.days)

}

exp_timeline[["electrophysiology"]] <- data.frame("protocol_day" = str_c("day #",

c(1:ephys.days)),

"date" = my_stamp(e.ds))

}

if (exists("e.ds")) {

exp_timeline[["total_days"]] <- e.ds[ephys.days] - start.date

} else if (exists("b.ds")) {

exp_timeline[["total_days"]] <- b.ds[b.testing_days] - start.date

} else if ("i.ds") {

exp_timeline[["total_days"]] <- i.ds[intervention_days] - start.date

}

#a final piece that is often a good idea to include (but not always strictly

#needed) is to tell the function which object to return() as a result

return(exp_timeline)

}Then we can use the new function by calling it like any other R function (plan_bn_exp(args)) and check that the output is the same. Doing things this way has the big advantage of letting us focus on the parts of the planning that we need to, i.e. the key parameters of our experimental design (assuming our experiments follow consistent protocols). It also reduces the chances that we’ll accidentally break the code when editing it to input the values (as we might via the non-functional version above) .

fun_exp_timeline <- plan_bn_exp(start_dmy = "07-09-2020",

intervention_days = 28,

behav_days = 28,

n_groups = 4, group_n = 12)

#rather than print it all again, I'll just check to make sure the output is the

#same

all.equal(exp_timeline, fun_exp_timeline)## [1] TRUENow you’ve learned a bit about how R programming can help you automate the process of planning a behavioural neuroscience experiment. If you were going to build a package around a function like this you’d want to do things a bit differently, but that’s a story for another post. If any grad students in psychology or neuroscience labs are reading this, some of you may even be looking forward to how much time you’ll save with these new time-processing skills under your belt. Student or not, after reading this I hope you can see that working with dates in R can be pretty easy when you leverage the lubridate package and you’ve even learned a few ways that they may benefit your research.

14 Notes

If you want to go beyond basic date-based operations and calculations and can’t wait to learn about related analytical techniques like time-series analysis & forecasting, I highly recommended checking out Forecasting: Principles and Practice by Rob J. Hyndman and George Athanasopoulos at Monash University.

If you can’t wait to learn more about how to write your own R functions, you may be interested in this chapter of R4DS

Thank you for visiting my blog. I welcome any suggestions for future posts, comments or other feedback you might have. Feedback from beginners and science students/trainees (or with them in mind) is especially helpful in the interest of making this guide even better for them.

This blog is something I do as a volunteer in my free time. If you’ve found it helpful and want to give back, coffee donations would be appreciated.